Ecosystems and fire exposure of the central UP

Goals

Using freely available LANDFIRE data, we take a look at the Central Upper Peninsula (CUP) of Michigan, plus some adjacent areas in Wisconsin to:

- Quantify and compare the dominant ecosystems of the area, past and present

- Explore how much ‘late-successional’ habitat would have been in the area past and present

- Map out areas with the highest wildfire exposure risk, contextualized by historical fire regimes

The area and approach

As anyone who lives in the central Upper Peninsula of Michigan knows, it’s a place where temperatures can range from well below zero to above 100 degrees Fahrenheit (though that is rare), snowfall can total more than 200” in a single winter and where leaves are on the ground for longer than they are on trees.

The ecosystems range from very dry jack pine barrens to northern hardwoods (includes sugar maple and yellow birch trees) growing on relatively fertile and well-balanced soils to wetlands (such as alkaline swamps with cedar and tamarack trees).

Many landscapes are very heterogeneous, meaning that you can easily walk, ride, ski or drive through many ecosystems in a short time. For example in the Yellow Dog Plains (north-central Marquette county) it’s possible to traverse those aforementioned ecosystems in a short distance. Here we explore where the ecosystems were, where they are today, where the late succession stages of those ecosystems are, and where wildfire exposure risk is the highest. Through harvests, prescribed fire (and fire suppression), altering water flow (e.g. through road development), we are changing these ecosystems. Some specific examples include:

- fires historically ‘cleaned’ fire-adapted ecosystems such as the northern pine-oak system, periodically removing needles and branches (i.e., fuels) that accumulate on the forest floor. Fire suppression halts this ‘cleaning’, leading to an accumulation of fuels. Prescribed fire and some types of harvest can reduce fuel buildup.

- road systems can alter water flow (hydrology) in multiple ways: 1) capturing and redistributing precipitation into ditches, 2) blocking flow when culverts are plugged, 3) increasing/decreasing water on either side of a road depending on natural direction of flow (so called ‘damming effect’) and 4) changing in temperature (which can lead to changes in organisms and chemical processes).

- tree harvests can result in obvious effects depending on type of harvest including: altered species composition, reduced overall tree height and canopy closure. These changes can in turn impact soil development, understory species composition, wildlife habitat and fuels accumulation.

We do not answer questions such as ‘where should we do fuel reduction projects to reduce wildfire risk’ or ‘should we set-aside areas that will not be harvested’ in this web report. Rather, we present background information that might help managers with those and other related questions. More specifically, we:

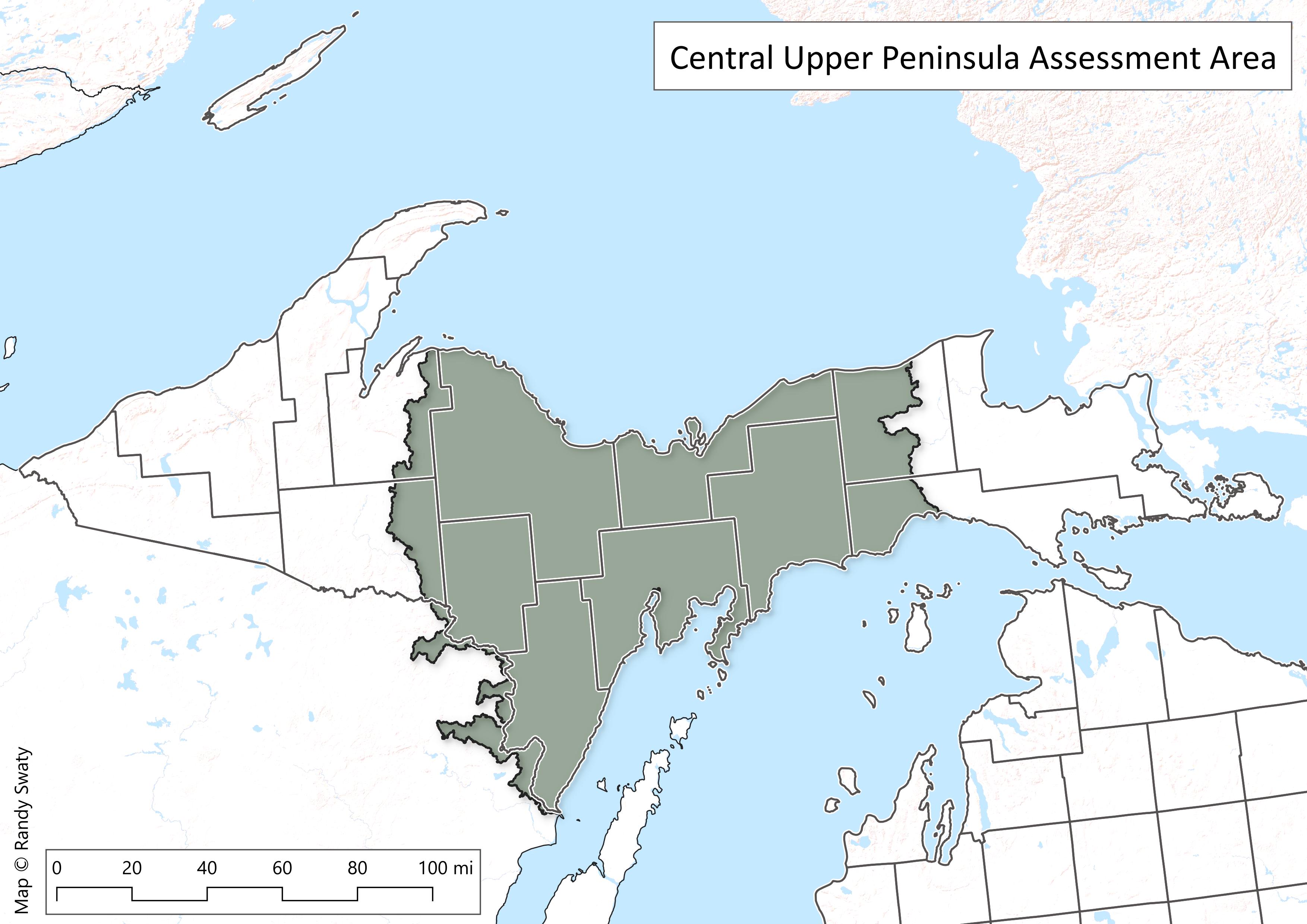

- Worked with planners from Marquette County to determine the ‘area of interest’.

- Formatted, summarized and displayed freely available datasets to depict ecosystems past and present, late-succession habitat past and present, and wildfire exposure risk.

- Organized the information into this web report.

For more information on methods and input data see the ‘About’ page.